By the Detroit Historical Society – Telling Detroit’s stories and why they matter

This year the GMRENCEN will celebrate 40 years of standing as the centerpiece of Detroit’s skyline. However the initial seeds for the Renaissance Center go back slightly further, to November 20, 1970. This was the date that the Detroit Chamber of Commerce convened a meeting of prominent Detroit business figures and political leaders, bringing together the likes of Henry Ford II and Max Fisher with Mayor Roman Gribbs and Governor George Romney. Dubbed Detroit Renaissance, this committee’s aim was to encourage economic growth and development in order to open a new chapter in this city’s story in the wake of the unrest and devastation of 1967. The group quickly set its sights on the city’s riverfront as a location for a major development project which could act as a catalyst for further improvements.

The construction of the Renaissance Center was arguably one the most significant, visible and enduring projects undertaken by resilient Detroiters during this difficult time our region’s history. This summer, a number of projects and events will mark 50 years since the uprising occurred including a major exhibition called Detroit 67: Looking Back to Move Forward that opens at the Detroit Historical Museum on June 24. This comprehensive effort looks back at 100 years of the city’s history and invites the community to help define what moving forward looks like in the fifty years that lie ahead.

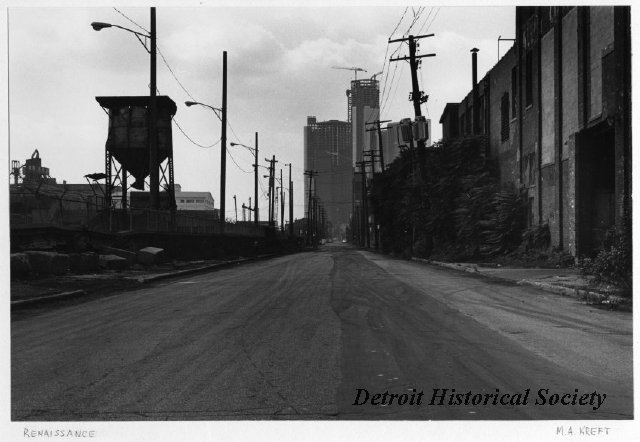

Today, in the shadow of the GMRENCEN, Detroit’s River Walk is crowded with joggers, cyclists, anglers, and folks out for a stroll, however for much of the city’s history the riverfront was an industrial strip. The Civic Center developments of the 1950s helped to reclaim a segment of downtown’s riverfront with Civic Center Park, Cobo Hall, and Ford Auditorium. Through the 1960s, planners hoped to extend their attention further west with a stadium complex as part of the city’s multiple bids for the Summer Olympics. After the Olympic flame moved on, planners intended that this complex would become home to both the Lions and Tigers. Detroit Renaissance initially also pursued the riverfront stadium plan, but with repeated rejections by the Olympic Committee, Tiger Stadium too dear in the hearts of fans, and Pontiac courting the Lions, the project was not to be. Instead Detroit Renaissance turned their attention to the east side of the Civic Center, a swath primarily containing warehouses, and free of residential properties.

On November 24, 1971, Henry Ford II presented Common Council, as the City Council was then called, with a proposal for the site—a towering hotel, office, and retail complex. Architect John Portman was an obvious candidate to make this proposal a reality. In the 1960s, Portman’s Peachtree Center was born from the Forward Atlanta effort, which itself was a model for Detroit Renaissance. The centerpiece of Portman’s work in Atlanta was the Westin Peachtree Plaza, a cylindrical glass tower resembling the Renaissance Center’s Tower 100. The Peachtree Plaza briefly held the distinction of being the tallest hotel in the world, but Portman would soon after top himself with the Renaissance Center.

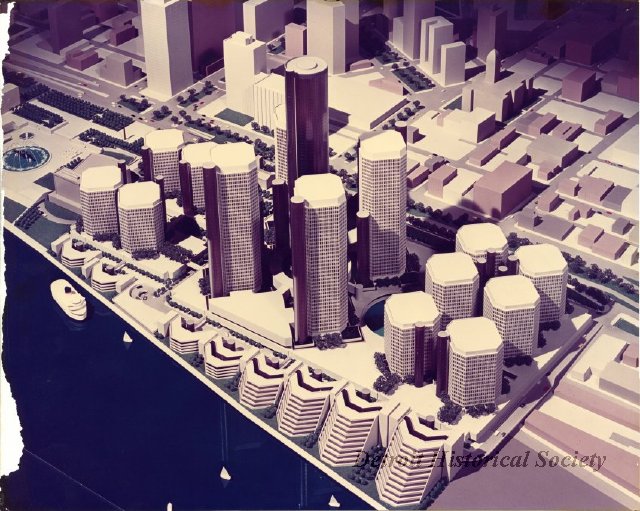

Early plans for the Renaissance Center showed a significantly more sprawling complex than the one Detroiter’s recognize. In addition to the present seven towers, eight more small towers similar to Towers 500 and 600 were proposed on both the east and west sides of the site. Additionally, a residential section with a series of terraced balconies would extend from the structure’s podium to the riverfront. Development of plans for Hart Plaza likely played a factor in the scaling back of these elements.

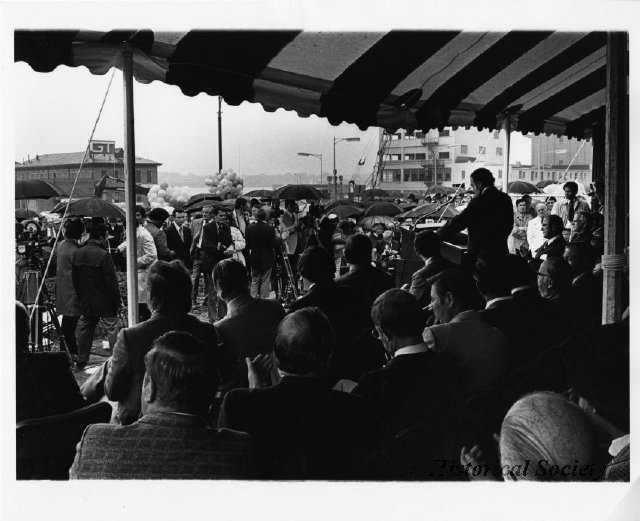

Even the present scaled-back plan for the site represented a significant undertaking. In order to realize the ambitious project, Ford assembled a coalition of 52 companies, including automotive rivals American Motors, and Chrysler. On May 22, 1973, at the groundbreaking ceremony, Ford and Mayor Gribbs addressed the crowd, flanked by representatives from these partner businesses. Rain clouds threatened overhead, but the Cass Tech band kept spirits high with a performance of The 5th Dimension’s “Up, Up and Away.” The duty of ceremonially turning the first shovels of earth fell upon a group of school children.

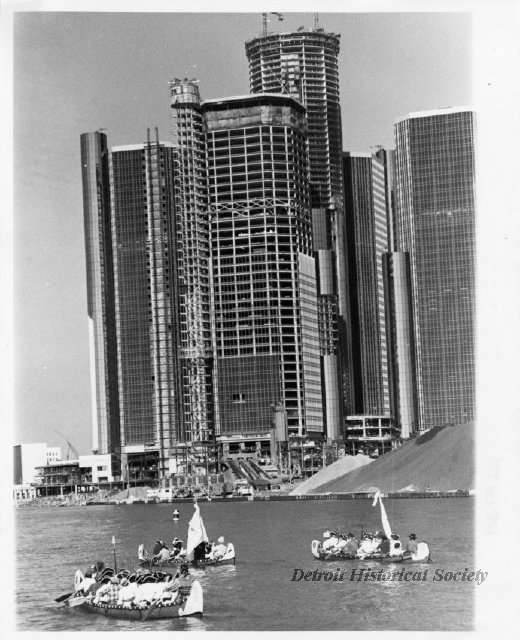

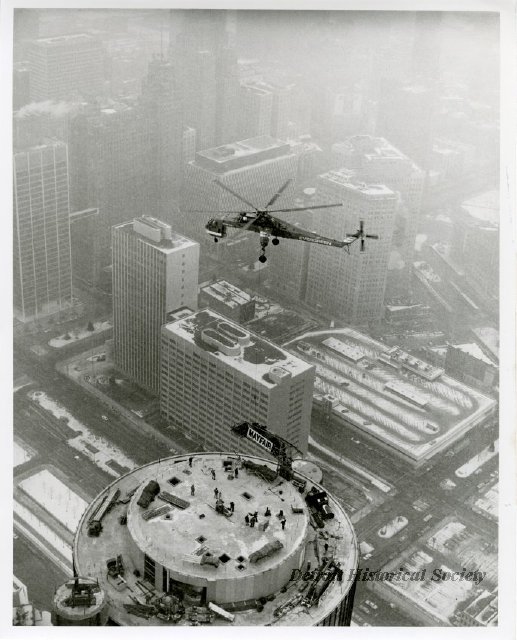

Even before it opened, the Renaissance Center had already become a star, as evidenced in several films from the Detroit Historical Society’s Detroit Video History Archive. The skeletal framework of the building appeared prominently in a public service announcement concerning the city’s new Emergency Medical Services, as well as a Metropolitan Detroit Convention and Visitors Bureau-produced film which urged viewers to “Take Another Look at Detroit.” As construction wound down, a promotional film about the new building was put together using detailed models of both the exterior and interior of the building. The film was set to a jazz-funk version of “Also Sprach Zarathustra,” as a none-too-subtle nod to the transformative power of the mysterious space monolith in the film 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Construction footage, close-ups of detailed architectural models, and a spacey soundtrack are among the highlights of this c. 1976 16mm film. Credit: From the collection of the Detroit Historical Society

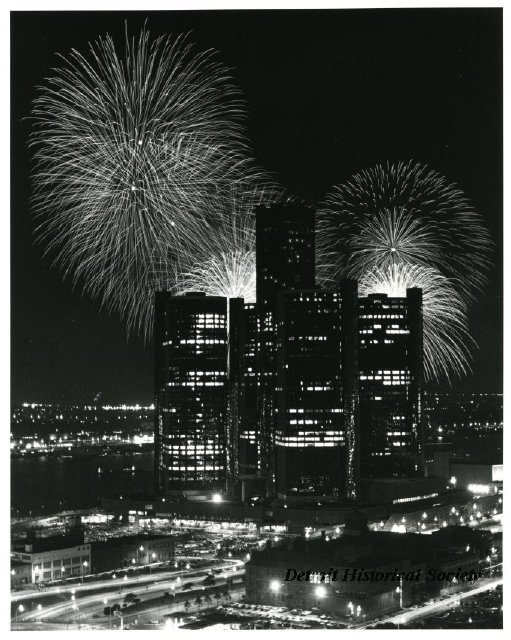

Construction on the Renaissance Center’s initial phase—the five main towers and the pedestal upon which they stand—lasted until April 15, 1977. On that day, the dedication ceremony was again attended by the city’s mayor, now Coleman A. Young, as well as Ford. Mayor Young also brought a surprising guest to the ceremony—Elio Gabbuggiani, the mayor of the original “Renaissance City,” Florence, Italy. Gabbuggiani’s involvement was controversial; he was a ranking member of Italy’s Communist Party, and Cold War politics almost dashed his visit. Young ultimately was permitted to extend his invite which resulted in the striking scene of Gabbuggiani and Ford—the Communist, and the capitalist—shaking hands.

Just two years later, in 1979, Ford announced a partnership with David Rockefeller to fund phase two of the project. Shortly after, workers broke ground on the additional two 21-story towers east of the original construction. Construction on this second phase wrapped up in 1982.

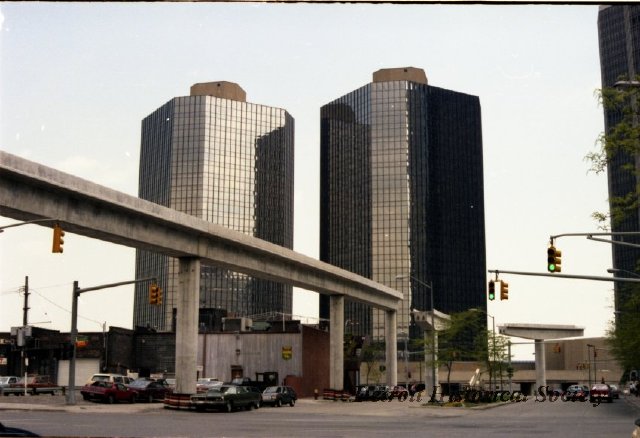

Although the familiar profile on our skyline was then in place, further smaller additions and renovations would be made over the next decades. In 1987, as the Renaissance Center was turning ten years old, a one-thousand slice cake was enjoyed by guests, while workers put the finishing touches on the first significant addition to the building—the People Mover station above its Jefferson Avenue face. On the Jefferson Avenue side, the large concrete berms that housed heating and cooling equipment were removed. On the river side, the Wintergarden area was added connecting the building to the new River Walk. Additionally GM added color-changing lights and LED displays on the exterior of the towers. In 2015, the updated building was official redubbed the GMRENCEN.

The GMRENCEN now enters its fortieth year. It remains as strong of a symbol for the city as the Old English ‘D,’ or the giant bronze fist of Joe Louis. What will the next forty years hold for the GMRENCEN?